“Catch a wave and you’re sitting on top of the world.” ~The Beach Boys

Last month I wrote about developmental waves related to language and early literacy. I shared how my little one and I created learning opportunities at the beach. We explored storytelling by the seaside. This month the topic relates to how young children develop and learn math skills.

Families can play a role in their child’s math development. I had a chance to talk about this topic on my University of Wyoming College of Education podcast episode #3 entitled, “Working with Families.” I shared some of the research my colleagues and I have been doing, as well as practice oriented strategies to partner with families of children. Math opportunities could also be embedded into activities like a day at the beach or children’s familiar routines. While playing with toes on feet, we could embed math concepts. For example, we could count toes on each foot and create playful moments with storytelling.

Developmental waves with math occur during familiar routines, play, and small and/or large group activities. Embedded learning opportunities could be planned or spontaneous. Learning opportunities could be child-directed or adult-directed. There are many ways we can teach children who are developing their math skills. University of Wyoming professor of mathematics, Dr. Scott Chamberlin, spoke about how math skills could be taught on the BUTTERCUP podcast episode. Curriculum of all types can be considered for supporting math learning in young children. For example, the AEPS-3 has a Math area can be used with a curriculum and assessment.

Early childhood professionals can support children’s math development by using a high quality curriculum-based assessment that has undergone research. The AEPS-3 incorporates authentic assessment in math with a companion curriculum to teach the targeted skills for children with and without disabilities. There are crosswalks created for state early learning standards, For an example of how Wyoming state learning standards align with the CBA see the Wyoming math alignment here (click). https://aepsinteractive.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/AEPS-3-Wyoming-Early-Learning-Standards_FINAL.pdf

For other state math alignments, see website. If you’re interested, click on the link below that will take you to the math blog I wrote about the AEPS-3 for Brookes Publishing. Link to Math information here: How AEPS-3 Supports Early Math Skills in Young Children.

When my daughter was in kindergarten she came home from school one day with a self-portrait entitled, “Math About Me.” It was a life size cut out of her holding a poster. On the self-portrait poster it showed how she saw herself portrayed in math concepts. She personally represented math ideas (e.g.., like how many?) and what they meant to her. Here are the six ideas that were represented on her hand drawn poster:

· I am 6 years old.

3+3=6

5+1=6

4+2=6

6+0=6

· I was born on this day….

· I have ___ pets.

· There are ____ people in my family.

· My favorite number is 3.

1+2=3

3+0=3

· I have lost 3 teeth so far.

The Montessori approach has many ways to create math learning. Dr. Maria Montessori was trained in Rome to become a medical doctor. Her early work was with children who were experiencing homelessness, as well as children with delays/disabilities. Her philosophy of education was revolutionary at the time, and she believed children had a right to high quality early learning experiences.

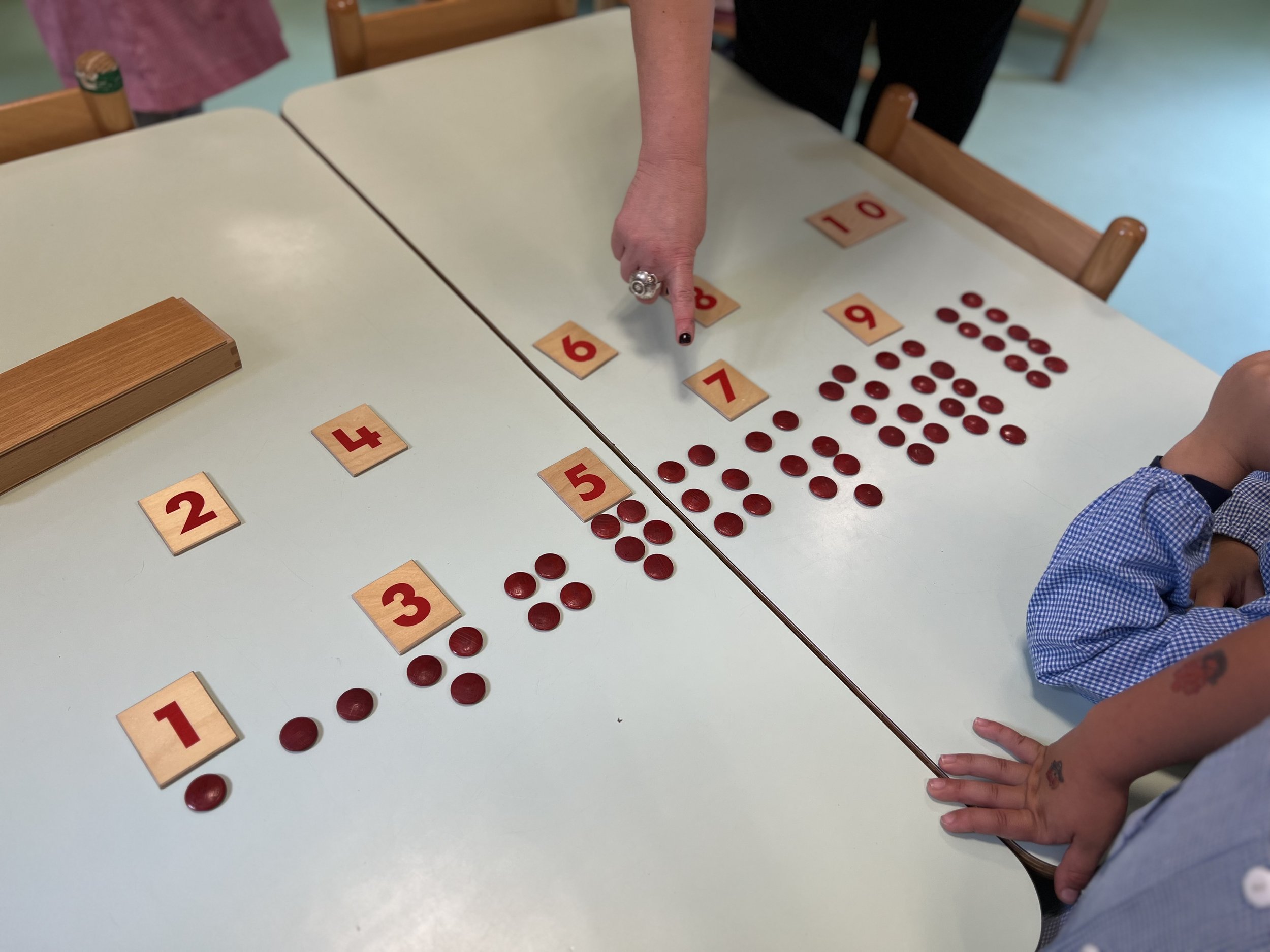

While I was in Italy, I had a chance to visit preschoolers in a municipal Montessori school. Children were learning about math using Montessori materials with their trained Montessorian teachers as shown in some pictures below.

Preschoolers in a municipal Montessori school in Italy exploring math concepts.

Montessori materials in a municipal Montessori school in Italy.

Montessori materials in a municipal Montessori school in Italy.

Preschoolers in a municipal Montessori school in Italy exploring math concepts.

Preschoolers in a municipal Montessori school in Italy exploring math concepts.

Preschoolers in a municipal Montessori school in Italy exploring math concepts.

A picture of Dr. Maria Montessori hangs in every classroom at the municipal Montessori school I visited in Northern Italy.

Two educators, Fred Rogers and Loris Malaguzzi, must have also had a love of numbers. Mr. Rogers, from United States, had his #143. It was his way of saying, “I love you” with math.

1 (I)

4 (love)

3 (you)

Loris Malaguzzi, from Italy, is known for his famous poem, “No Way. The Hundred Is There.” Some of the lines from his poem are:

“…a hundred languages

a hundred hands

a hundred thoughts

a hundred ways of thinking

of playing, of speaking.”

1+4+3= Fred Rogers

💯 + 💯 + 💯 + 💯 and 💯 more = Loris Malaguzzi

For the love of numbers and children, why not make some waves with math moments today.